In school, children are first taught to master the basics – what we used to call the “Three Rs” – “reading, writing, and ‘rithmetic”. These areas are widely understood to be the fundamentals of education, and without them a student cannot progress to higher levels of learning or reasoning.

The same can be said of investors. Many of today’s investors have been drilled in the basics of return and risk – or volatility, the traditional definition of “risk.” We know that there is no return without some risk, and we evaluate how much risk is palatable given our objectives. In years past, these two “Rs” were sufficient to succeed. But today’s investors know that isn’t the case anymore, and a third area is necessary to outperform in the future. The third R is resilience.

Resilience isn’t taught as a core principle of investing, but it should be. Investors today, particularly institutional investors that manage others’ money over longer horizons, must meet expectations that go well beyond hitting a target rate of return with a given level of volatility. Meeting these expectations means being able to adapt to unforeseen events or paradigm shifts, and incorporate objectives beyond return. These objectives may be related to targets on climate, progress on diversity and inclusion practices, limitations due to geopolitics, and many other issues.

When investors ignore these other objectives, disruption often occurs – usually enough to cause the investor to make costly changes at the worst time. Building portfolios that are resilient to changing expectations or guideline for how return is earned is critical, especially for investors with very long-term horizons.

Modern Portfolio Theory, as introduced by Harry Markowitz in 1952, taught us about risk and return and the “efficient frontier.”

This was the start of “two dimensional” investing. Prudent investors seek to build efficient portfolios – those that maximize expected return for a given level of expected risk. A portfolio with scope to target a higher return with the same level of risk – or the same return with lower risk – is considered “inefficient” it lies below the efficient frontier. Prudent investors could choose different combinations of risk and return along that line, but never below it.

During the second half of the 20th century, before Modern Portfolio Theory was fully incorporated into investment decision-making, there were likely many inefficient portfolios. But as tools improved, fiduciaries recognized that targeting efficient portfolios was both more beneficial and their duty. There are some drawbacks to such an approach, but the goal of building an efficient portfolio along return and risk targets is now universally accepted.

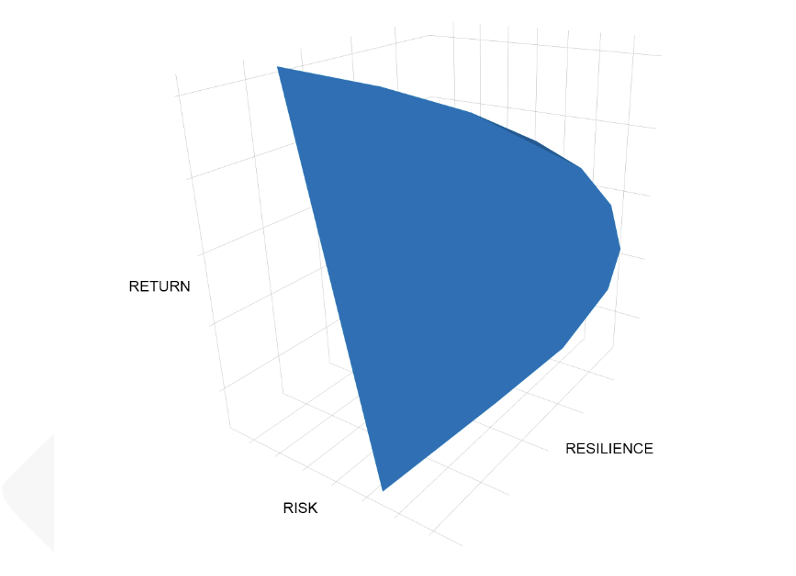

Today, in light of changing expectations and aided by new information, we are now considering how to build efficient portfolios on three dimensions: risk, return and now resilience. Rather than a simple two-dimensional curve, think of a building with a large, curved roof. Points along the axis are efficient combinations of risk, return, and resilience. As in Modern Portfolio Theory, prudent investors could choose different combinations of risk, return and resilience along this line. However, choosing a portfolio inside it – one in which risk, return, or resilience could be improved without affecting any of the others – would be inefficient and imprudent.

A three-pronged optimization of a portfolio isn’t a new idea. Investors have long been aware of a “3-D framework”.

In fact, a 2019 study from AQR Capital Management proposed a theory in which each stock’s ESG score both (1) provides information about firm fundamentals and (2) affects investor preferences. The solution to the investor’s portfolio problem is an “ESG-efficient frontier”, showing the highest attainable Sharpe ratio for each ESG level. Roger Urwin has called 3-D portfolio frameworks that incorporate impact “a game changer”.

For fiduciaries, it may be more intuitive to consider resilience than ESG or impact. If an investor has made a net-zero commitment, for example, then perhaps their measure of resilience is their carbon footprint, as they will be unable to hold investments with high carbon outputs over time. If the investor could meet the same risk/return targets with better resilience, why wouldn’t they do so?

Similarly, an investor may be concerned about being able to hold investments in certain countries over time due to geopolitical implications. If there were similar investments in countries without such risks, it would make sense to adjust their portfolio.

There is a lot of discussion today about whether sustainable, “ESG”, or net-zero portfolios entail trade-offs. The answer is that it depends on where the portfolio starts. Given how new this line of thinking still is, it is likely that the portfolio is inefficient by the standards of our three-dimensional frontier. In that case, there is no trade-off at all, and there may in fact be Markowitz’s “free lunch” of investing – building resilience by moving towards the “resilient frontier”. Of course, if the portfolio is already on the frontier, there will be trade-offs to increase resilience, just like there would be trade-offs to add return or reduce risk.

Given that the role of a fiduciary is to optimize the portfolio for their beneficiaries over time, a prudent investor must try to be on that new frontier to fulfill their fiduciary duty – to maximize return with a given level of risk in a resilient manner. Even under US law, “risk-return ESG” is permissible in contrast to “collateral benefits ESG”.

Some may say that this is simply good investing. But as prior work in this area has shown, there is indeed a method to considering changing environmental, social, or geopolitical factors in the investment process. And it is necessary to build portfolios that are well-positioned to adapt to a changing world and prosper in the long term.