A version of this post was first published on Harvard Law School Forum for Corporate Governance and Financial Regulation. Thank you to our Member organizations who contributed to the writing of this article.

By now, most business-watchers have seen the president’s tweet asking the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to study the requirement that US public companies release earnings quarterly. With this message, President Trump has focused attention on the short-term mentality that too often characterizes American business.

The tweet, which followed his discussion with Pepsi CEO Indra Nooyi about how to better orient corporations towards a more long-term view, has provoked a flurry of discussion on how corporations can take a longer-term approach to business and investment decisions, and in doing so, fuel growth and innovation in their communities.

And rightly so. An analysis of publicly-listed US companies by the McKinsey Global Institute showed that companies operating with a long-term approach consistently outperform their peers on a wide range of metrics, including revenue growth, profitability, shareholder return and job creation.

Furthermore, a C-suite survey FCLTGlobal released with McKinsey and Company in 2016 is telling: 55% of CFOs admitted that they would delay NPV-positive projects in order to hit quarterly earnings targets. Clearly, too many capital allocation decisions are made without a full appreciation of the long-term implications—notwithstanding a few oft-cited exceptions such as Amazon. Most Americans invest their retirement savings in these companies, and they depend upon their success over several decades to enable them to retire with sufficient savings or pay for their children’s education.

While the detrimental effect of short-term behavior is real, shifting to semi-annual reporting in the US raises legitimate fears of a lack of transparency with companies only disclosing significant developments in their business twice a year.

There are four solutions that the SEC could explore to encourage long-term behavior while maintaining the disclosure that is critical to well-functioning markets:

1. Make it very clear that quarterly guidance is neither required nor desirable

2. Encourage companies to report progress towards their annual results rather than quarterly results per se

3. Encourage companies to provide long-term strategic roadmaps, recognizing that the future may not unfold as expected

4. Study pairing any relaxation of the quarterly reporting requirement with a strengthening of other disclosure rules to ensure transparency in markets.

Quarterly guidance is neither required nor desired

It is critical to distinguish quarterly guidance—forecasts issued by companies of future earnings metrics—from quarterly reporting, the retrospective look at how a company performed over the prior three months.

There is a common belief that quarterly guidance is advantageous to companies and investors—and it may have been in the pre-internet world of limited data and primarily retail shareholders—but today it is a relic. Many market participants even believe that quarterly guidance is required, which it is not, confusing the SEC’s encouragement of forward-looking information as promoting short term guidance. The SEC could more clearly underscore the distinction between quarterly guidance and quarterly reporting.

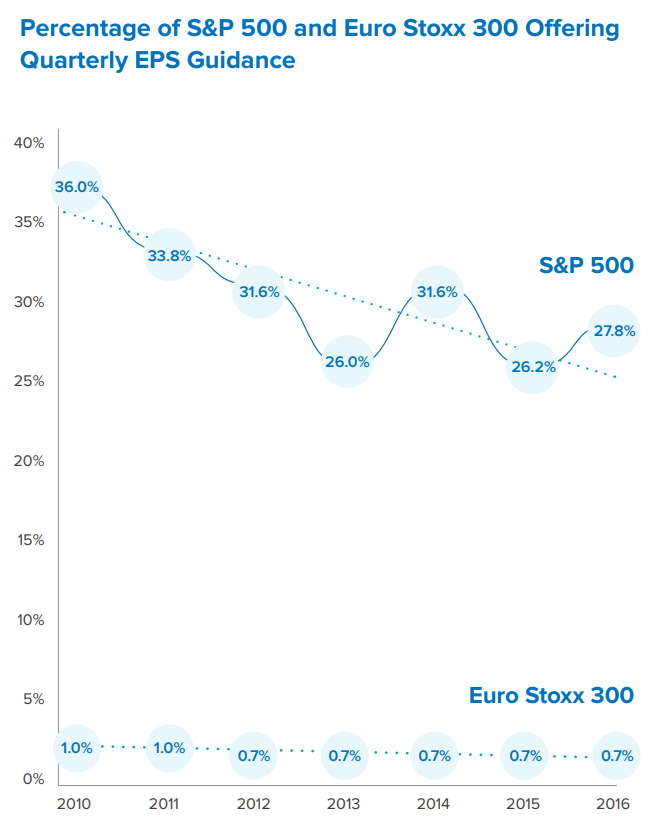

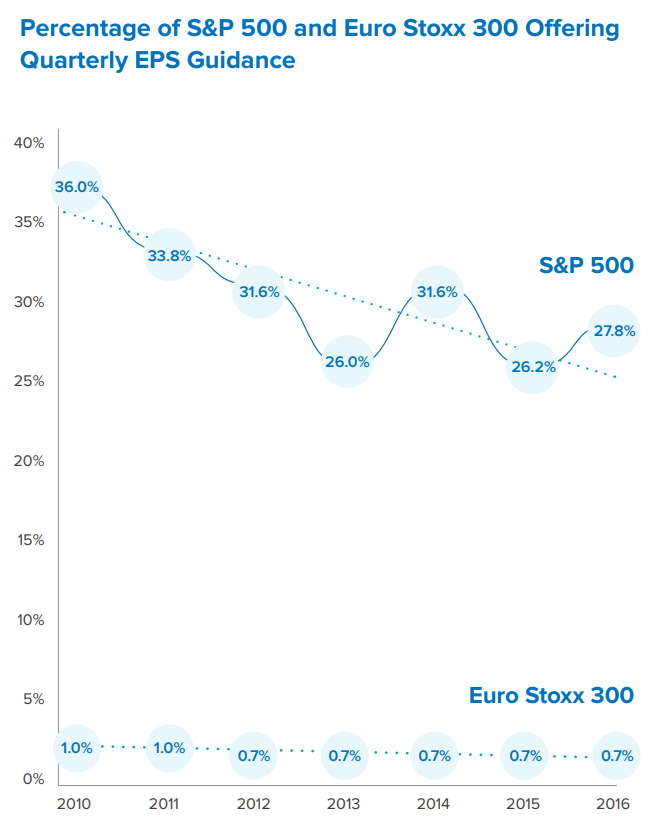

Guidance is already falling out of favor with American companies and is virtually non-existent in Europe. In 2016, for example, only 27% of the S&P 500 and 0.7% of Euro Stoxx 300 offered quarterly EPS guidance (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Source: Moving Beyond Quarterly Guidance: A Relic of the Past. FCLTGlobal, 2017.

Furthermore, there is overwhelming evidence that investors (as opposed to the media or other analysts) don’t like quarterly guidance either. According to a Rivel study, only seven percent investors are interested in guidance metrics for periods of less than a year. Similarly, an Edelman survey of institutional investors revealed that 68% agreed that providing long-term guidance positively impacts their trust in companies they are invested in or considering investing in.

My organization, FCLTGlobal, has also been vocal in its opposition to this practice. In addition to underscoring investors’ desire to move away from the practice, our research demonstrates that quarterly guidance has no impact on a company’s valuation and in fact increases, rather than decreases, share price volatility, particularly around reporting season.

Subsequent analysis from Bloomberg reinforces this: their analysis shows that for 7 out of 9 quarters between 2016 and 2018, companies who issued quarterly guidance (the guiders) experienced higher earnings surprise than non-guiders, while the differences between the two for the remaining quarters were immaterial.

FCLTGlobal’s position has been reinforced several times since our 2017 research was released, including in a powerfully-worded op-ed by Warren Buffet and Jamie Dimon, as well as by the National Investor Relations Institute and the National Association of Corporate Directors, both of which publicly support companies’ efforts to focus on the long-term growth of their business and the economy as a whole.

An SEC statement clarifying that quarterly guidance is neither required nor desirable could serve as the nudge American companies need to begin aligning their focus with long-term objectives. While it is unlikely that the SEC would ban the practice of quarterly guidance given its historical approach of enabling voluntary disclosure, it could nevertheless call attention to the problem, including by asking companies who do issue quarterly guidance to disclose the extent to which such practice creates a risk factor, whether the board and audit committee have discussed with management the pros and cons of providing such quarterly guidance and why the company believes providing quarterly guidance, as opposed to longer-term frameworks for value creation, is in the best interests of the company and its shareholders.

Reporting progress towards annual results rather than quarterly results

Another step the SEC could take is to encourage companies to report their financial progress towards annual results rather than quarter-by-quarter. Companies would report first quarter results, then half-year results, then nine months results and then finally results for the year without analyzing each quarter individually.

While anyone can do the math and compare quarter over quarter, we have learned from the behavioral economists how important framing is. Framing quarterly work as progress towards a longer-term goal is costless and could serve as another nudge for long-term thinking. When discussing quarterly results, companies would situate them within the broader context of the company’s strategy, longer-term objectives and a year’s worth of progress.

Providing long-term strategic roadmaps

We and others have been encouraging companies to develop clear long-term strategic roadmaps in place of quarterly guidance. Such strategic roadmaps can focus shareholders on a company’s longer-term plans and provide them with the opportunity to evaluate both the strategy and the management team’s execution of that strategy. Companies also have more flexibility in deciding the right metrics to use when conveying long-term strategic roadmaps. In a recent Financial Times column, Harvard Professor Larry Summers bolsters the case for providing long-term guidance by stating, “Wise corporate leaders should give a sense of their long-term vision on at least an annual basis. Investors who insist on such information are only being reasonable.”

The most common concern we hear about providing such strategic roadmaps is a legal one: that companies will be open to criticism if those plans do not come to fruition or if they need to pivot as market conditions change.

To assuage this concern, the SEC could provide clear direction to companies and investors alike about the parameters for providing long-term strategic roadmaps and any resulting liability, confirming that safe harbors for forward-looking statements and other protective measures will apply to such long-term outlooks. Having long-term oriented dialogues between companies and their shareholders supports the allocation of resources to productive long-term uses.

Strengthening intra-period disclosures

There are many examples of countries that do not require quarterly reporting. These countries have often paired less regular financial statement reporting with stringent continuous reporting of significant changes to a company’s business. This continuous reporting framework offsets the concern that less frequent financial reporting will lead to either very significant, discontinuous disclosures every six months or the opportunity for insider trading.

It would certainly be appropriate for the SEC to study the issue of quarterly reporting as the president suggested. It can do so by examining the requirements in other countries, such as the UK and Australia, for continuous disclosure, and looking into whether today’s Form 8-K framework in the US for “current” reporting of specified material events should be broadened to enable less frequent reporting of full financial statements. Reporting is essential to maintaining transparency for all shareholders, and mechanisms such as making on-going disclosure requirements more robust could be appropriate.

The UK’s recent experience in changing reporting frequency is also worth noting. It now requires only half-yearly reporting, reversing a 2007 decision to implement quarterly reporting. Both domestic and foreign investors encouraged the shift, and there are a number of major institutional investors who continue to encourage the UK companies that report quarterly to stop the practice. Research from the CFA Institute indicated that for the periods studied and using their methodology, the frequency of financial reporting had no material impact on the levels of corporate investment, so relaxing quarterly reporting requirements is not a panacea for short-term thinking. However, their research also showed no impairment of analysts’ ability to forecast corporate performance, assuaging some concerns about the impact of reductions in the frequency of reporting.

Summary

We commend any attempt by the White House, the SEC, and American business to combat short-term pressures in our capital markets. While considering various reporting standards is certainly a legitimate exercise, the evidence for addressing quarterly guidance is much stronger than for addressing quarterly reporting and merits close review.

By encouraging the elimination of quarterly guidance, the reporting of progress towards annual results, and the issuing of long-term strategic roadmaps, the SEC could have a very significant impact on short-termism even within the current regulatory framework.

Sarah Williamson is the Chief Executive Officer of FCLTGlobal.